Hi everyone! After completing my summer internship at the Vance Birthplace, I wanted to share with you some of my thoughts about my final project and how it went!

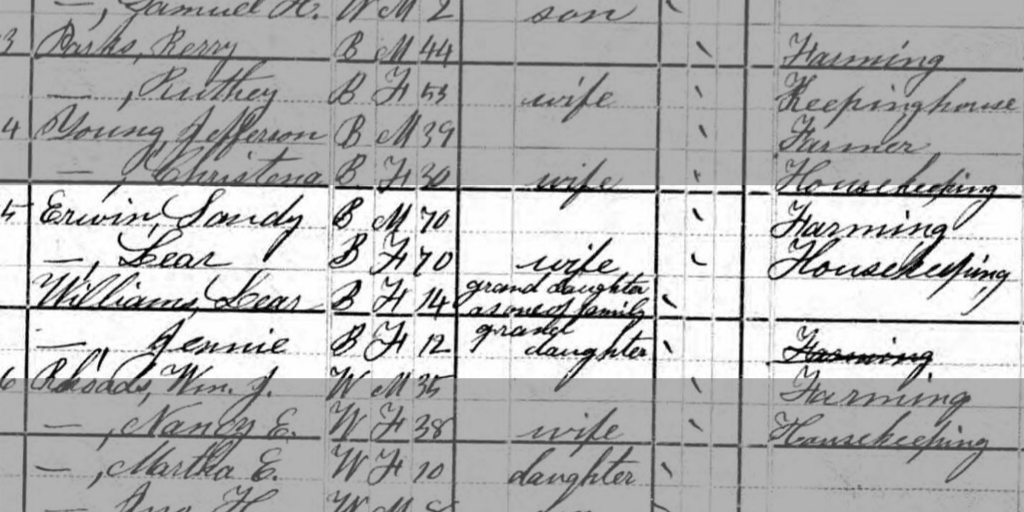

My project for the summer was to create a virtual timeline about the lives of some of the women who lived and worked on the site throughout its history. I focused on the Cherokee women who were on the land before the Vance family, Priscilla Brank, Aggy, Venus, Leah Erwin, Mira Baird, and Elizabeth Hemphill. The project is set up as a timeline covering when these women were on the site. I created the project using Sutori, which is an online presentation format that is mostly for teachers and students, but that I found worked well for my purposes for the site.

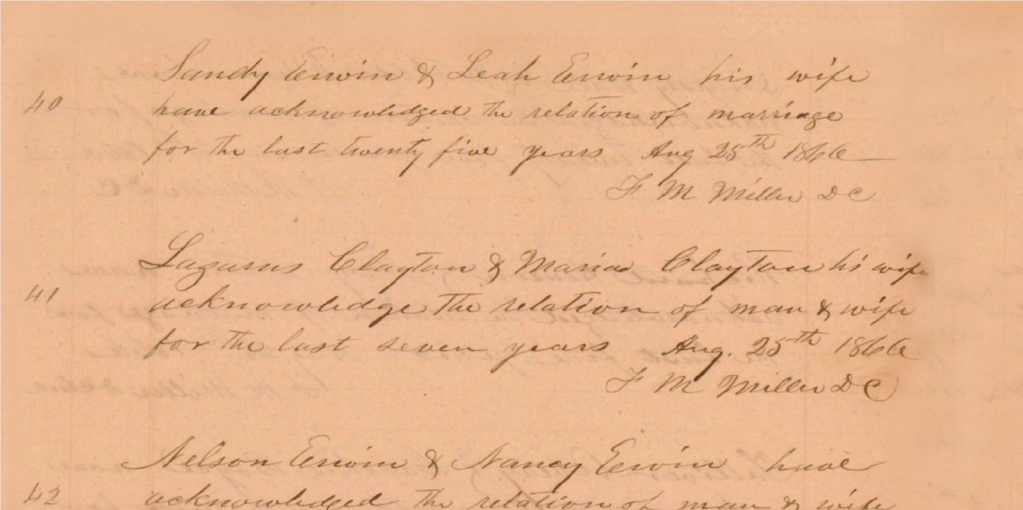

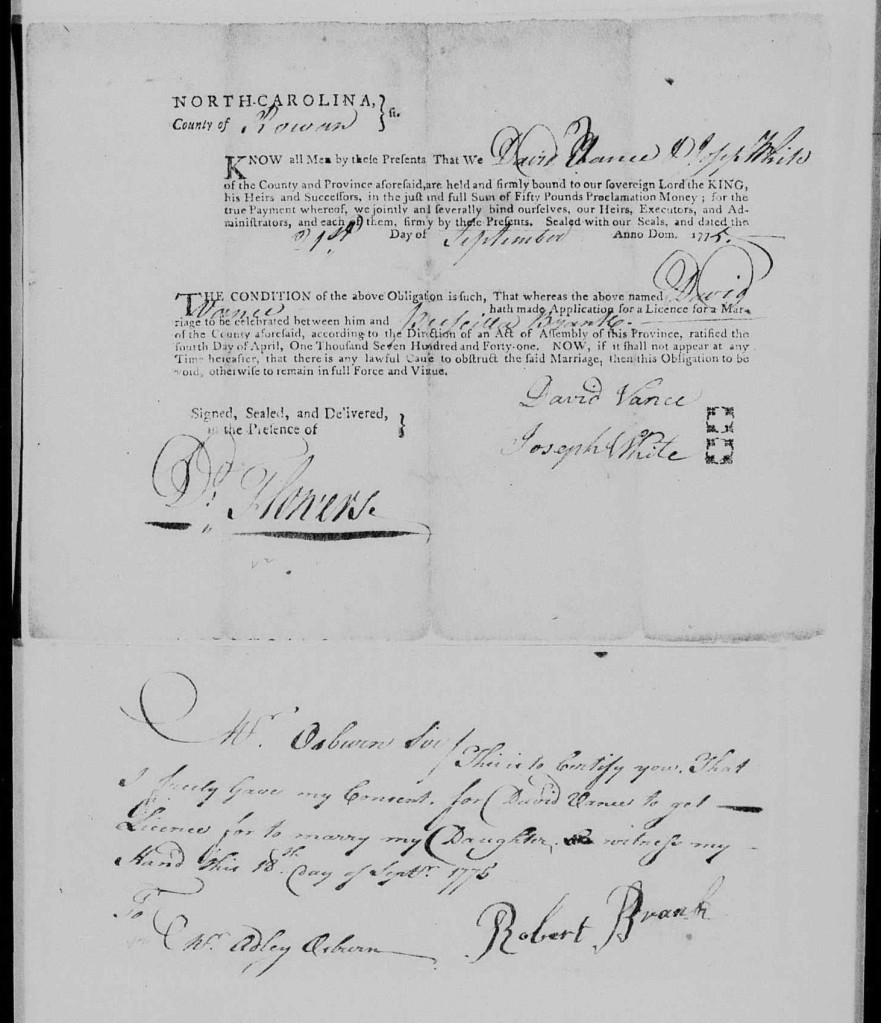

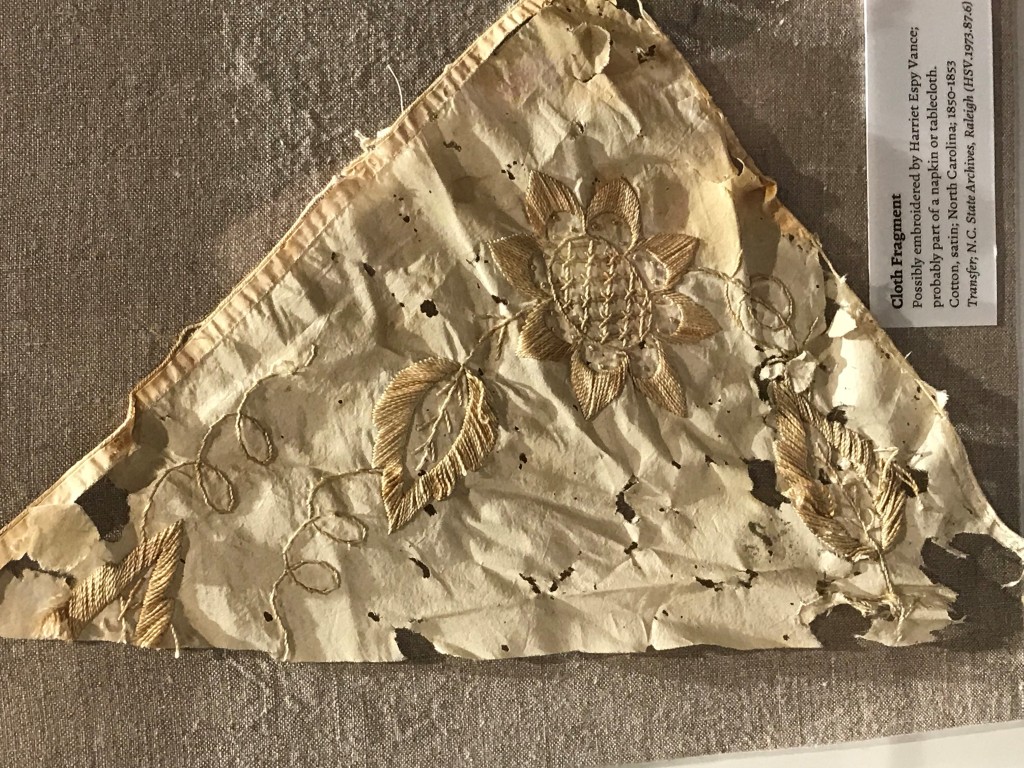

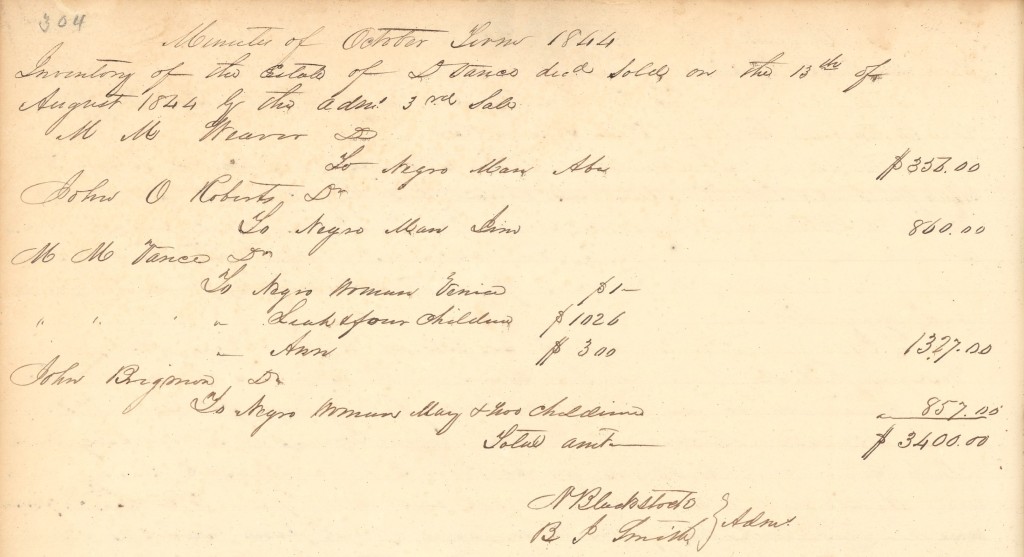

In order to accurately tell these women’s stories, I had to research the primary documents and photographs available to me through the Vance Birthplace itself, since most of the little we do know about these women, especially those who were enslaved, comes from those documents. The 1844 estate sale of David Vance Jr, as well as a letter written by Mira Baird Vance, were extremely helpful in my research. Outside of these primary documents, secondary research on the historical context for the experiences of these women was most important. Before I completed this project, I knew very little about women’s history in southern Appalachia and in Asheville specifically. I had to read relevant chapters in books related to the history of North Carolina and the history of women in North Carolina, in order to get a broader sense of what their lives would have been like.

Of course, for enslaved women, my research had to become even more specific, so that I could make sure I was presenting an accurate, full, and honest narrative. I had to confront my own whote privileges when discussing slavery, and make sure that I was not imposing my biases onto the stories of these women, to the best of my ability. I also learned a lot that I didn’t know about the history of slavery in America, and the history of enslaved women, and how their bodies have been used throughout history as a means of promoting oppression.

Some books I found to be most helpful when learning about enslaved women’s lives in America and specifically in North Carolina, were Instances in the Life of a Slave Girl by former enslaved woman Harriet Jacobs, Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century by Tera W. Hunter, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, and North Carolina: Change and Tradition in a Southern State by William A. Link. I would encourage any of you who are interested to pick these books up, as they are easy to follow and really teach you a ton about the history of slavery and racism in our nation.

My research for Priscilla Brank Vance was particularly interesting, because there is so much context for her lifetime that needs to be understood in order to fully create a picture of what her life would have been like. There is just too much to include in the project, to be honest. Her parents lived through the French and Indian War as adults, and she lived through its aftermath as a child. She was the daughter of German immigrants, and she married a soldier in the Continental Army, who was away from her fighting for long periods of time. She was an enslaver and also a woman living through the events of the American Revolution and the creation of a new democratic nation. The conflicting ideas of freedom and slavery during this time could not have been lost on her, especially since, as a woman, she was denied many of the freedoms that the founders of this country advertised during the revolution herself.

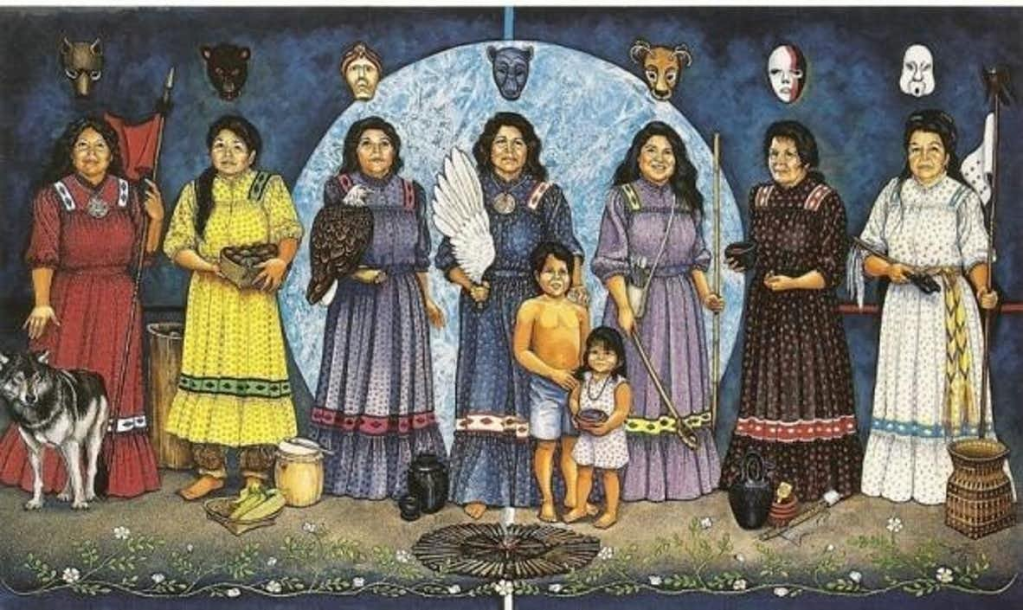

Another more interesting group that I researched for this project was the Cherokee women who lived in the Reems Creek Valley before white colonists arrived. Unfortunately, I knew very little about these women before this project, but that means that I learned the most when researching their culture and experiences. I found Theda Perdue’s book Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700-1835, to be invaluable for this research, although several of the books I thought would be mostly related to the histories of African American and white women in America gave me some great insights into the lives of Native American women, especially the Cherokee, as well.

I think the most challenging part of this project was the virtual aspect of it, and the fact that I had to spend hours on a computer during the day researching. In hindsight, if I had more money to spend, I probably would have bought some physical copies of the books I read, instead of reading ebooks, just because it would have saved my eyes and head some pain! Of course, that was simply the nature of doing a public history internship during a global pandemic, and I am grateful for the experience of creating virtual material and for being able to work with a historic site! Many of my peers could not get an internship this summer, virtual or otherwise, because of the crisis.

Another challenge was learning to write to a public audience with various ages and reading levels, and different levels of historical knowledge, instead of to an academic audience of fellow historians. I have been trained for so long to write like a historian, but I have only been studying public history for a year now, and so I lack the training in how to write for a museum. This means, however, that this project gave me much needed experience on that front!

My favorite part about the project however, was simply learning about these women’s lives. I think that, as a future professional historian, I get so focused on completing my research and making a historical argument or writing the perfect paper, that I forget to just enjoy learning the history I am reading about in the first place. Due to the virtual nature of this work, and the fact that I needed to present it to a diverse public audience with various interest levels in history, I knew I would have to approach it differently. I focused on teaching myself in order to effectively teach the public about the topic, and I looked for interesting facts to include that would catch viewers attention and help them remember these womens’ stories.

Overall, this project was really rewarding, and I plan to add to it in the future if possible, as I find out more about the women who lived in the Reems Creek Valley, who deserve to have their stories told.

You can visit the completed timeline on the Vance Birthplace website: https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/zebulon-b-vance-birthplace/history